Tarsila do Amaral : Painting modern Brazil,

The work of twentieth century painter Tarsila do Amaral, who derived inspiration from sources as varied as Fernand Léger’s iteration of cubism and the Social Realism movement, is synonymous with Brazilian modernism. Highly celebrated by the most esteemed artistic circles of her time, Amaral– often referred to simply as Tarsila– is gaining traction with a contemporary, international audience thanks to exhibitions like Tarsila do Amaral: Peindre le Brésil Moderne, on view until 2 February, 2025 at the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris. Both Tarsila’s denunciation of Eurocentrism in the arts and her radical approach to fusing styles seem to resonate with modern audiences, as evidenced by the enormous success of the 2018 MoMA exhibition titled Tarsila do Amaral: Inventing Modern Art in Brazil. The Musée du Luxembourg show sustains this conversation about the painter’s legacy, bringing together more than 150 works spanning her lengthy career. It’s the first time a retrospective of Tarsila’s work has been displayed in a major French museum and a striking testament to the ways in which the artist’s oeuvre was progressive in terms of both style and subject matter.

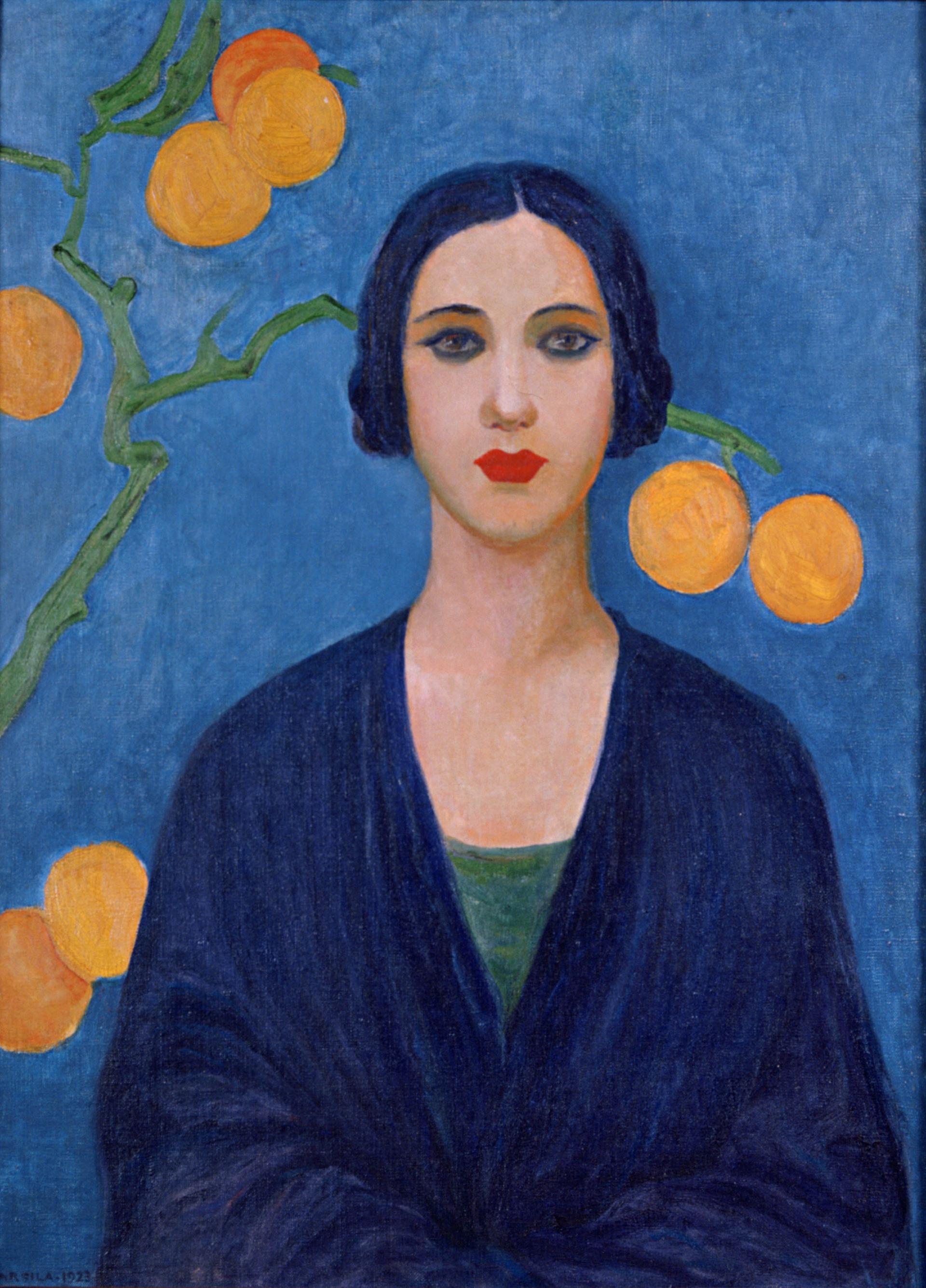

Born to an affluent family in São Paulo, Tarsila cut her teeth in Paris studying under the pioneers of Cubism. Her distinct flair, characterized by vivid colors, rounded forms, and smooth finishes, is a product of cultural cross-pollination, as she spent much of her early career alternating between Brazilian and European hubs of artistic production. The issue of honoring and shaping Brazilian identity was of utmost importance to the artist, and its centrality in her work is made evident by Tarsila do Amaral: Peindre le Brésil Moderne. Tarsila is perhaps most well-known for her participation in the Anthropophagic movement, conceived of in the 1920s and later revived by artists and intellectuals in the 1970s. The term anthropophagy, in the context of Brazilian culture, was coined by Oswald de Andrade in his Pau-Brasil manifesto to signify the “cannibalizing” of other cultures as a means by which to establish Brazilian national identity and combat European colonialism. Disparate influences, ranging from indigenous artistic traditions in rural Brazil to modern Spanish surrealism, converge on the canvas to form a uniquely Tarsila vocabulary. Her early paintings often depict dreamscapes, defamiliarized human bodies, and exaggerated natural motifs inspired by the verdant, rural regions of her home nation. In the latter half of her career, after encountering Socialist Realist painting in the Soviet Union and engaging with leftist causes, her work adopted a political inflection; she took great interest in the struggles of migrants, workers, and Brazil’s most oppressed populations, depicting their daily lives in a precise, restrained style.

At first glance, the somber laborers and grim smokestacks present in her mature paintings seem like a sharp departure from the lush, vegetal imagery that frequented her earlier works. But the impetus for their representation is analogous: Tarsila sought to amplify Brazil’s popular consciousness and folklore traditions equally, and to make manifest on the canvas the convergence of styles and cultures that accompanied rapid modernization. She’s remembered both as champion of oft-overlooked indigenous symbols and practices integral to Brazilian culture and as an innovative, technically sophisticated painter. With Tarsila do Amaral: Peindre le Brésil Moderne, Musée du Luxembourg honors her as such.