exhibitions

see more

PAST EXHIBITIONS

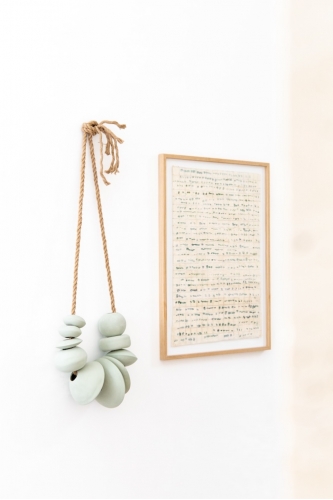

virginie hucher

Anima Mundi

July 2022

Behind the forms lie organic backgrounds, shaped by washes of paint and rubbing. Their asperities give them a tumultuous and lyrical appearance that contrasts with the entities they host. Like waves or quicksand, they move and disperse, seemingly on the brink of evaporating completely were it not for the grid or line motifs anchoring them to the reality of the canvas. The grid is frontal and neutral. During the Renaissance, theorists used the grid as a system to construct perspective in images. In a famous text, Grids, published in 1979 in the journal October (no. 9), Rosalind Krauss analyzes the grid motif, exploring its contradictions: on one hand, it is a pure and essentially modern form, while on the other, it retains the remnants of a symbolic window that, in her words, "masquerades as a treatise on optics." She writes, "The mythical power of the grid lies in its ability to persuade us that we are in the realm of materialism (sometimes science, logic) while simultaneously plunging us into the domain of belief."

This union of opposites is intrinsic to Virginie Hucher's work. The grid, in this context, reflects both pure immateriality and a connection to textiles, craftsmanship, and even language and femininity. Repeated in an all-over pattern, it combines a quasi-mathematical logic with a poetic sense of space and time. There is no intent, in this practice, to decide whether the sacred or the material will dominate.

In the midst of these gridded backgrounds, centered on the canvas like talismans, Virginie Hucher's shapes are full and rounded, yet recurrently penetrated by more or less deep notches. These softly hollowed areas seem to provide fertile ground for anything that might slip into them. A blind force appears to be carving its way through what resembles embryonic silts or furrows—natural contoured forms conducive to nourishing life. Retractable like snail horns, these entities simultaneously turn outward: they extend their appendages toward the edges of the canvas, multiplying into one, two, or three forms, according to principles of cellular division or parhelion—an optical atmospheric phenomenon in which the sun appears to double or triple.

The absence of scale prevents any definitive judgment on the nature of the vision. Operating on both microcosmic and macrocosmic levels, it is more a pictorial cosmogony where the painter seeks not so much to represent nature as the phenomena underpinning it. "To paint a tree, become that tree," says Virginie Hucher. "If you wish to show this leaf, feel the sap that makes it grow." Pictorial animism, one might say.

Moreover, the forms remain identical from one canvas to another: while their surroundings continually transform, they retain the same "soul," as though metempsychosis were not limited to living beings but could also apply to geometric forms. In this perspective, the dualism opposing body and spirit, sacred and real, spiritual and material, traverses both abstraction and figuration. Abstract forms, too, are animated and active, composed as much of matter as of lines. This is evidenced by the quasi-sculptural plasticity of the artist’s work, which tends to replace the brush with non-traditional tools—sticks, utensils, or the hand and forearm—that scrape the pictorial surface, imbuing it with a prophylactic, or protective, force. These abstract forms are alive.

Elora Weill-Engerer

Art Critic, Member of AICA

Exhibition Curator, CEA

May 2022