exhibitions

see more

PAST EXHIBITIONS

"Tout ce qui nous rend libre"

Juliette Lemontey

May 2023

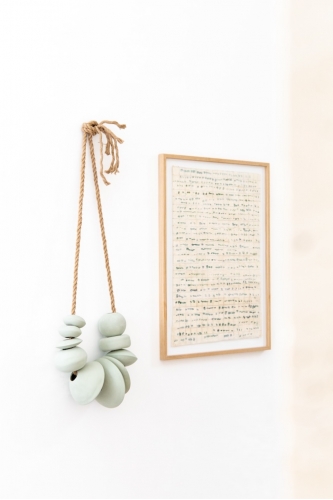

One does not enter inside the other as one would like. This is what Juliette Lemontey's faceless bodies say. In his non-reflexivity, the faceless person is outside of social relationships, the deliberate obliteration of the face distancing him from his relationship to the other. The covering of the orifices by the skin shows the reverse side of a dream of fusion of the bodies and the face, walled and smooth, is a warning against whoever would try to reach it. Is this a possible translation of what prosopagnosia would look like, the disorder of face identification? Or opening the moment to those who would find something familiar? For, at the same time as personal identity is neutralized, it is replaced by the identical and the common narrative. Stripped of its stigmata, the face becomes a surface of projection, a backdrop where images surge. The memories of something very slow and silent that belong to all of us are pressed into it: vacation love, family reunion, school outing, so many anonymous memories of fading bodies that are close to disappearing in time. History repeats itself, permanently. Our genes carry our emotions, our experiences and our traumas and, in this sense, a life can continue after it is forgotten. This is not without engaging nostalgia. The fragments of bodies mark the absence and a poetic incompleteness that the German Romantics understood very well with the ruins.

The walnut stain, more or less diluted, stains the face in question with asperities, as if it had been washed away, dissolved under the action of a cloth that wipes away the past. The skin, we know, wears out with time, in an inexorable aging that seems already contained in the supports that Juliette Lemontey uses. The artist works on mottled canvases and sheets of second life. These fabrics, dotted with oxidation stains like fairy tears, also serve as a frame for the painted canvas, giving it the status of an object with which one would have lived. Their apparent weave and their little fluffy things effectively place the work under the sign of touch and intimacy. They call to mind the fabrics that our grandmothers used to spread everywhere, even in the wallpaper. Their light color, beige, fades with time, like a flower. One of the possible origins of the term indicates that the beige designates a "fabric of natural color" (Le Littré), before defining by metonymy this particular natural color. What is visible is also matter. It is what we find until the dense and dark hair that halo the heads of which they underline the oval and of which Baudelaire said that the hemisphere could contain a whole world. The buns, headbands and braids are capillary canopies that prevent these beings from completely disappearing: they tie them firmly to the memory. Together with the patterned clothes, they contribute to give an old-fashioned je ne sais quoi to these stolen scenes. Everything is protection, envelope and cocoon on Juliette Lemontey's paintings. These sheets, soothed by the ghost of a loved one, have the scent of whole days spent in bed where even gestures enter a vegetative cycle. We can hardly remember them in their entirety. We can hardly put a face to them.

Elora Weill-Engerer